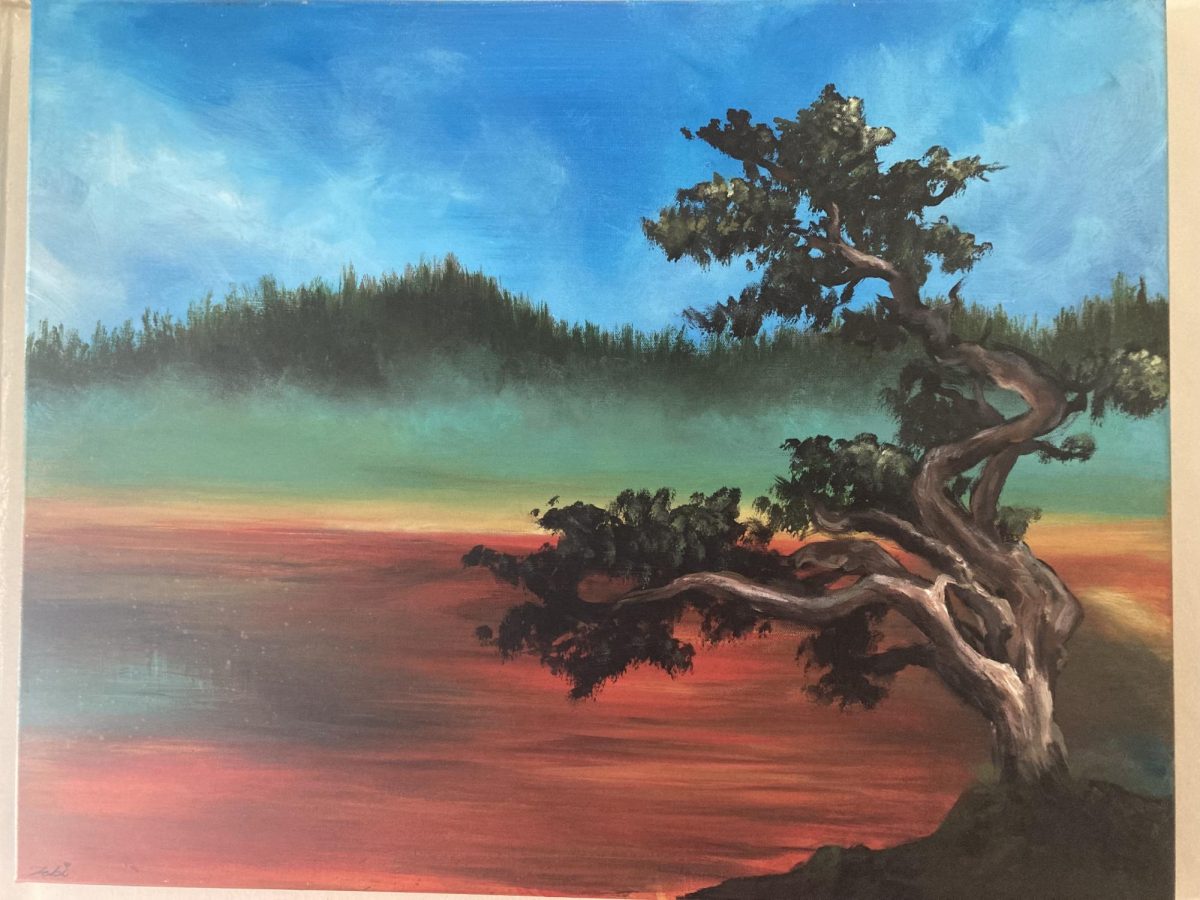

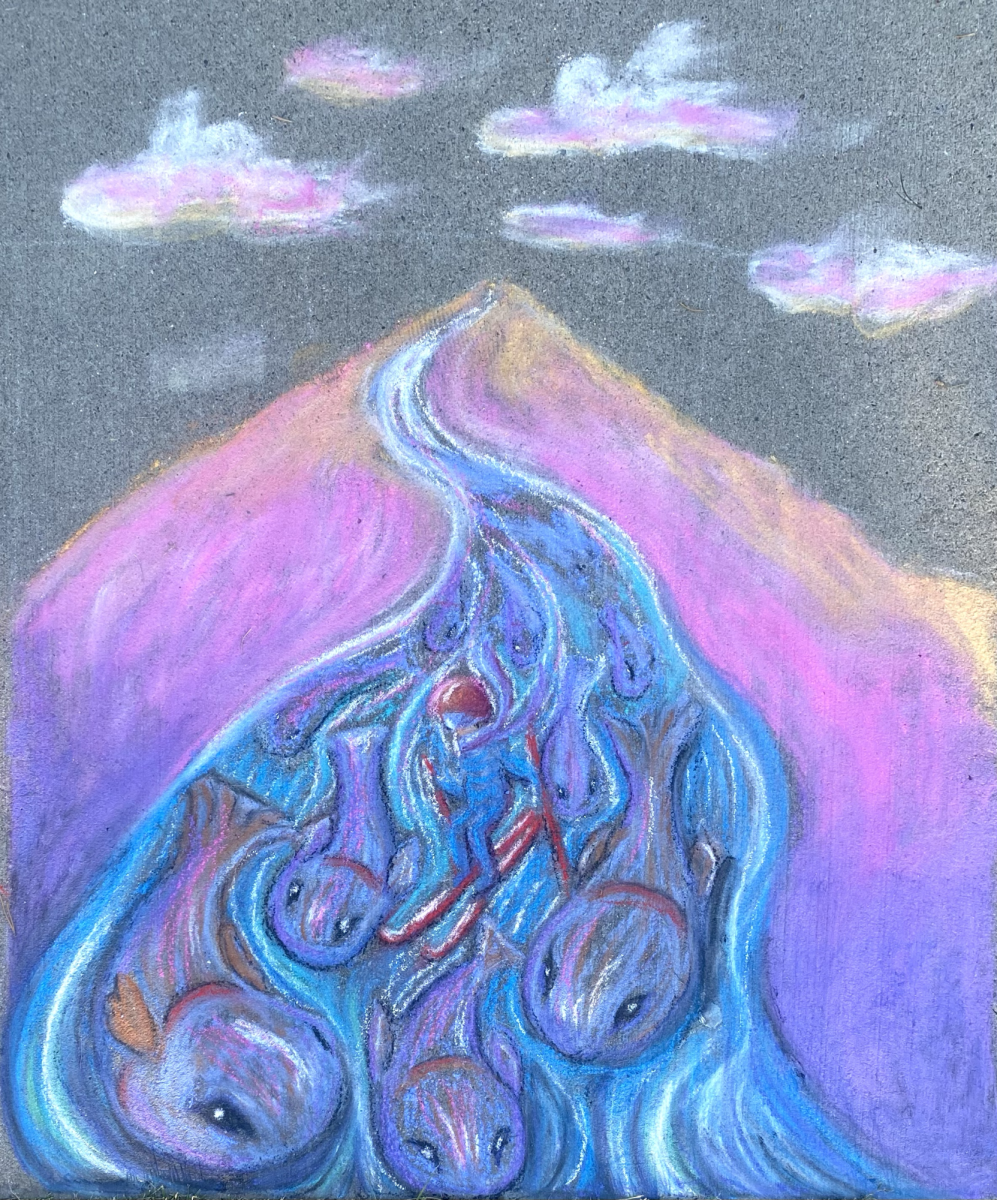

Photography by Brook Ferris

Ode to Growing Out My Hair Again

B. Hannah

I learned how to braid hair

at a friend’s eighth birthday party,

crossing thick chunks

of golden yarn over a brick wall.

My hair reached my hips then, dark clouds

hanging low over hills stretching

from my body, the earth,

and I would spend hours with

my fingers twining soil-dark strands

like hazel switches around each other.

My mother didn’t know what my

name meant when she gave it to me —

I think of it as an honorific as

I count black inches of hair

each month in the mirror. Hill, it means,

black-haired, it means, drop of

water. A different mirror watched

me slice it off at the nape

of my neck in an age-old February,

a Snow Moon marked by a

black-attire-affair.

I can try to clarify; when we

grieve, or change, we cut our hair.

As long as I knew her,

my grandmother’s

hair was short and white, so

thin you could see her scalp. She

smelled like rain. Drop of water.

She lived by a pond, on the edge of a

forest, and when I was young

I wished she were a witch,

the kind who makes soup

in a big cast-iron cauldron

in winter, the kind who grows lettuce

and daffodils in the front yard.

She had a way with letters. She liked

purple dresses and pearls

and long, spidery handwriting,

and she liked my long, long hair.

Black-haired girl, with braids like

ancient weapons, warrior

unearthed by eastern air.

After the birthday party,

I went home and taught my mom

how to braid her hair,

because she had never learned,

because her mother’s hair

was always short, a perpetual

period of mourning. Her father had

no hair either, had shaved it

all off when he left Oklahoma.

My mother keeps her hair long now,

lets her curls show,

hides the gray with red paint and busy fingers,

and I watch her weave.

Here is my ceremony:

each night before I sleep, I flip

the pillow over once. I watch

my chest rise like a hill — Hill —

from the earth. I picture myself

in purple dresses and pearls,

hair like arrows hanging over my hips.

Brook Ferris

Biography: Born in Alaska’s rugged beauty, Brook has been immersed in photography for over half of her life. Her upbringing in this inspiring setting fostered an early appreciation for the storytelling power inherent in a single image.

Now based in Oregon, her work challenges societal norms by focusing on systemic violence and gender equity, particularly in male-dominated professions. Brook’s photography blends personal narrative with broader social commentary, exploring themes of identity, resilience, and justice.

Whether capturing Alaska’s landscapes or documenting human experiences, her work invites reflection on the ties between place, memory, and the forces that shape our shared histories.

Artist Statement: These images reflect my connection to Alaska, where I grew up, exploring “roots” through natural and historical lenses. Each image integrates the wild landscapes, human presence, and cultural background that shaped my identity.

From untouched landscapes to abandoned structures, my photographs reveal how the land and its people are interconnected, highlighting the resilience that defines Alaska.

This work invites viewers to consider their roots—both as places of origin and as ties to larger histories and ecosystems. Alaska’s landscapes are not only my roots but an embodiment of how place and memory are inherently linked in shaping who we are.

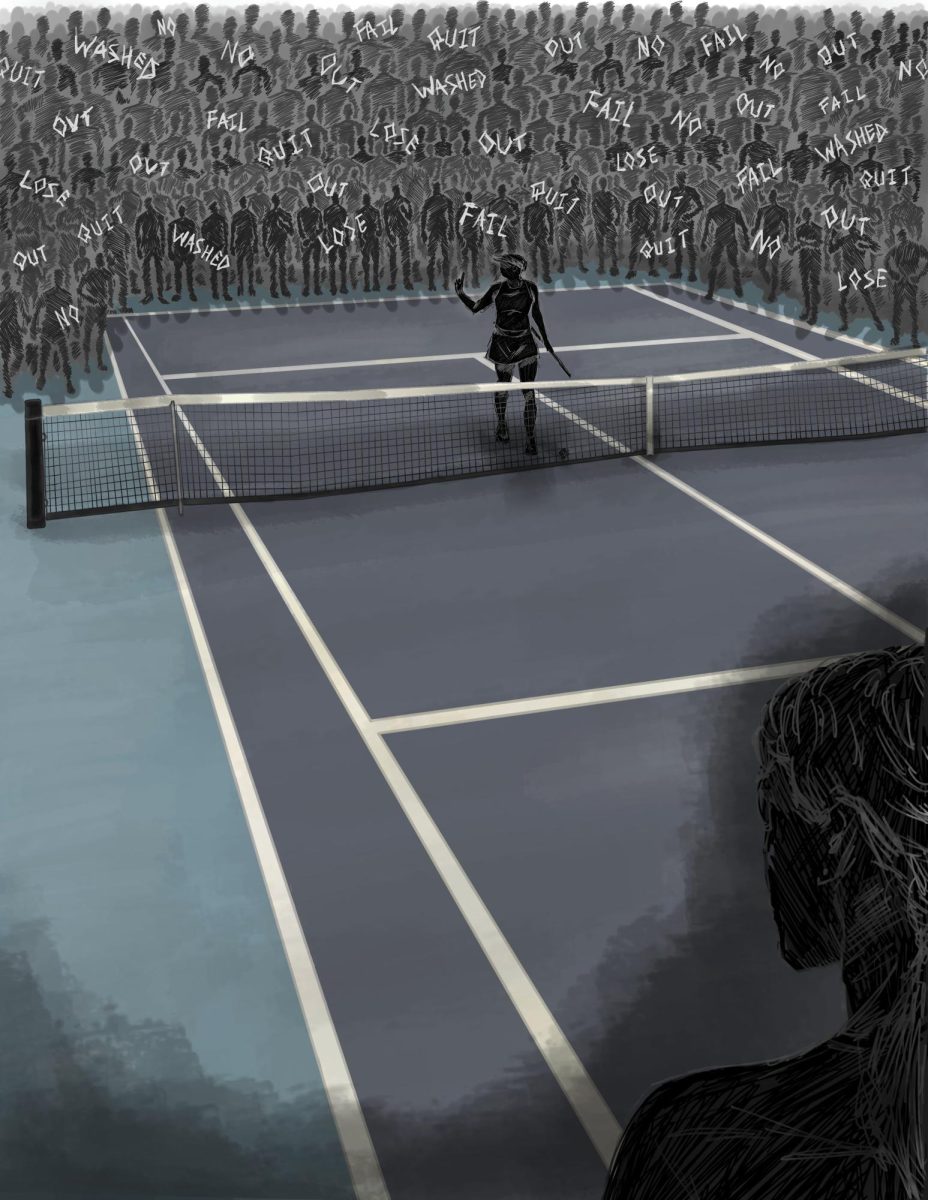

B. Hannah

Biography: B. Hannah is a senior creative writing, Indigenous studies, and German student at OSU. As the legend goes, she’s a storyteller who wandered her way into writing poetry and has been unable to find her way home (not that she’s complaining). She loves to incorporate her love of linguistics, her Cherokee culture and heritage, and her connection to her hometown of Las Vegas into her writing. She is the winner of the 2024 Provost Literary Prize in Poetry and has been featured in the past two issues of PRISM. She’s known for reading too many books about witches.

Artist Statement: For many Indigenous people, it’s traditional to cut our hair when we’re in mourning. I had very long hair for most of my life, but cut it all off for the first time when my grandmother died. I kept cutting it for years because I felt that I’d gone through some changes that kept me in mourning. My grief wouldn’t leave me alone. This poem traces my desire to grow it out again and so release that hold on my grief.