CONTENT WARNING: this essay includes sexual images, including images of partial nudity, BDSM and torture, as well as discussions of torture, murder and rape.

As the practice of book banning grows at a fevered pitch, with sexually suggestive and explicit material being one of its greatest targets, it’s easy to wonder — why now? Were we always okay with books about sexuality and have become more conservative, or are books only becoming a little slutty now?

The Heritage Foundation, the force behind many of their book bans, broadly explained their push against “pornographic” content under the umbrella claim that they aimed to “Restore the family as the centerpiece of American life and protect our children,” as stated in Project 2025. If that’s something we’re restoring, then were our libraries once homes of godly, family-friendly role models? Where have they gone?

A better question might be — what were these role models doing when we turned out the lights?

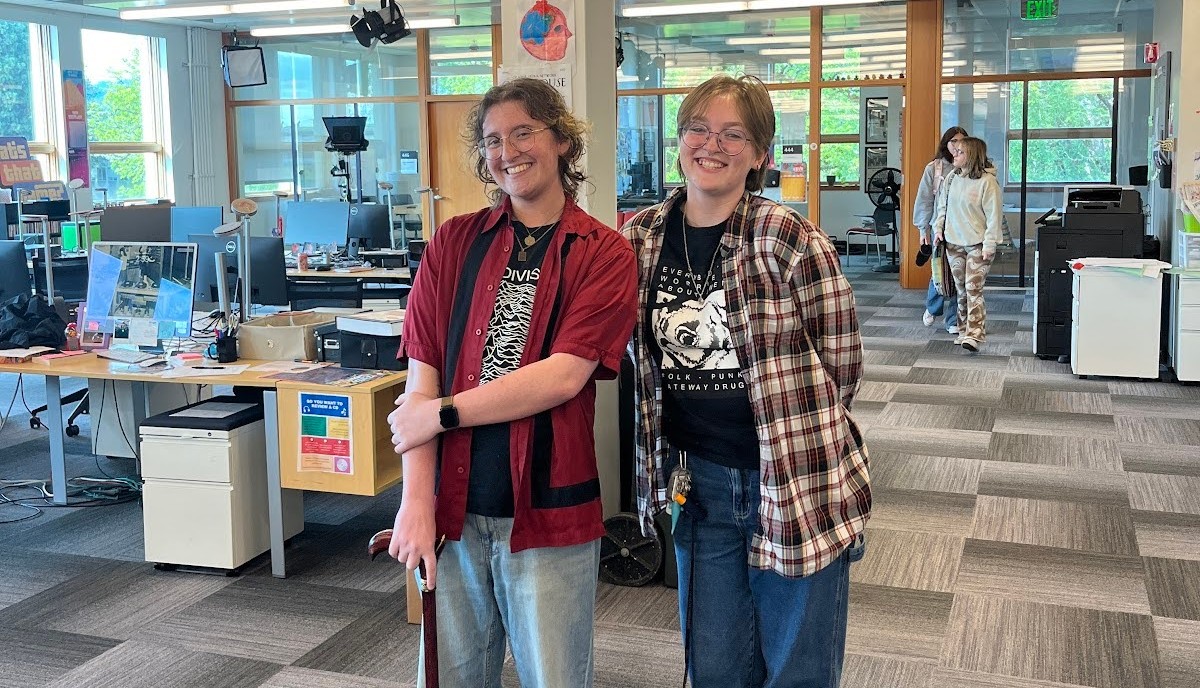

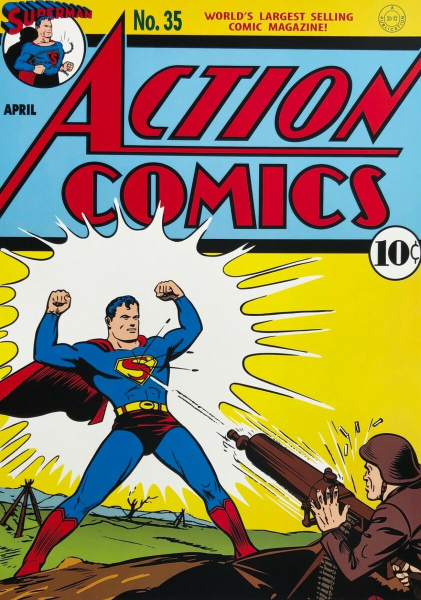

Take Superman, the American hero of the mid-20th century:

You probably recognize him, unless you’ve found a cozy rock to live under for the last century. He’s big, he’s strong, he saves ladies in distress. He’s a dominant force, in the kind, patriarchal way 1950s men are supposed to be. A great role model for any patriotic young man looking to waste away a Sunday afternoon with his head in his comic book.

And this is … uh … whoo boy.

This unnamed dude, with the same height, build, hair, face and illustrator as Superman, was created during a legal battle between said illustrator and Superman’s copyright holder. He’s big, he’s strong; I don’t think that lady is in distress, though. And … I think I’ve seen more dominant forces at the Co-op. Is the 1950s men we remember?

No?

What about this?

Huh, this is a little less Godly than the 1950s my grannie told me about.

But what about this?

Wait, where did the men go??

These images are from “Nights of Horror,” a collection of 1950s BDSM erotic comics illustrated by Joe Shuster, the co-creator of Superman. The story behind “Nights of Horror” is pretty tragic — Joe Shuster and his work partner lost the rights to Superman and fell deep into poverty, so he turned to making fetish art to keep afloat — but the images speak to a past far more complicated than media from the mid-20th century that dominant culture kept alive would suggest.

As a child, I remember watching “The Music Man” and “The Andy Griffith Show,” and being dazzled by the wholesome world they depicted. Handsome, strong men sweeping sweet, doe-eyed women off their feet, providing for adorable nuclear families in perfect little suburban neighborhoods — it looked simple, easy. The presumed gender roles underlying them, the dominant man ruling as benevolent king of the household and the submissive woman following his wise counsel in return for his protection and adoration, didn’t bother me when I saw how happy those women seemed.

Then I grew older, and my vision of the mid-20th century warped. I learned about the horrific normalisation of domestic abuse during this era, the legalization of marital rape and the extreme financial restraints put on women, in addition to the lack of civil liberties for nearly every other marginalized group. Helped by music videos like “Whiter/Straighter” by Adaline, “Let it Go” by The Neighborhood, and “It’s my Life” by No Doubt, I began to see the mid-20th century as a woman’s hellhole. But the overarching gender dynamic that I saw in that era — that of strong, dominant men and weak, submissive women — didn’t really change. Until I discovered “Nights of Horror.”

True, some “Nights of Horror” strips live for this dynamic; a great deal depict restrained women being humiliated and even tortured by men. But the men are usually ugly, brutish and/or old; they’re drawn to be evil, not the proud, paternalistic heads of household the 1950s exalted. It’s hard for me to imagine that the male artists, or the male readers, meant to see themselves as these men.

So where are the attractive, alluring, Superman-esque men in “Nights of Horror”? There’s one place to look: the other end of the whip.

This dynamic isn’t found in “Nights of Horror” alone. In the cutesy-erotic comic strip “The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline” from 1974, author John Willie’s blatant Mary Sue character, Sir D’arcy, is a blundering fool who spends more time being insulted and humiliated by pretty ladies than partaking in his female friends’ neverending torment of Gwendoline.

And Eric Stanton, one of the giants of the underground fetish art community in the 1950s and friend of the creator of Spider-Man, made his views on dominatrixes public. “A woman has to be strong. The bigger the better,” he once claimed, and his art did not disappoint.

Almost more common than mid-20th century fetish art involving men being dominated by women were images and stories of women being dominated by women, or women alone. “Nights of Horror” lavished in the imagery of the helpless female form, with men relegated to props in the sidelines or dismissed entirely, while “The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline” focused almost exclusively on pretty ladies tying up other pretty ladies, and even Eric Stanton would allow a submissive woman appear on his pages if it meant he could draw another lady forcing her to her knees.

While I don’t want to overstep my bounds, I’m going to try to get inside your head for a moment. I’d bet you think comics like this one → are funny, while strips like this one ← make you uncomfortable, because the latter aligns with gross 1950s gender norms. And the w/w strips? I imagine those might feel icky, sort of male-gaze centric.

Maybe so. But people did — and people do, and people always have — had a wide array of kinks, some socially acceptable in their given society, some not. No matter how patriarchal or matriarchal a society, there have always been guys who like being stepped on and guys who like holding their girls on a leash, women who like being kept on all fours and women who like making grown men whimper. What these comics show is that real-life diversity of attractions, pushing against the strict gender and proprietary norms of the mid-20th century.

But we still haven’t answered our original question. If this sort of content has been created since our grandparents’ ages and beyond, why didn’t we know about it? “Nights of Terror” actually played a big role there.

The year was 1954 when a group of four teenage boys began roaming the streets of New York City on sadistic benders, whipping girls and attacking homeless people. Dubbed the “Brooklyn Thrill Killers,” the teens killed one man, Reinhold Ulrickson, by cracking his head open, but were not caught until later in the year, when they beat and drowned a homeless Black man named Willard Mentor and were finally arrested.

The case drew nationwide attention, and a psychiatrist was called in to see if one of the boys was mentally competent to stand trial. He was, but the psychiatrist remained to question the boys and learned that one of them supposedly read “Nights of Horror” (although there’s many doubts that this claim is true) while another liked reading “crime comics, you know, like Superman.” The psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham, declared that “Nights of Horror” was to blame for the crimes, even going so far as to say that “all the horrible details (of the beating, kicking and whipping committed by the Thrill Killers) are to be found in most of the comic books … I wish to emphatically point out that such crimes did not exist before this comic book era.” (I feel like I shouldn’t need to say this, but in a country founded on enslavement, beating, kicking and whipping human beings maybe existed before the 1930s). Wertham ignored the propaganda books the boy had admitted to reading, like “Mein Kampf,” and focused solely on comic books.

The resulting public backlash was huge. The New York State Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of Comics had already been created, but with the help of Wertham, they pushed Congress to ban the sale of crime and horror comic books in 1954, and a new book-destroying campaign began in New York with “Nights of Horror” as their most infamous, but far from their only, target. A legal battle ensued, and the Supreme Court eventually upheld the ban.

The ban didn’t last. You can see tits on TV now, and anyone can waltz up to the Corvallis Public Library to read a book of Gene Bilbrew’s vintage fetish art. Numerous murders have been blamed on numerous pieces of media (see “Invader Zim”) (“The Matrix”) (“The Catcher in the Rye”), and we’ve largely dismissed this excuse. Most importantly, the internet has connected anyone with a computer to endless pornography 10,000x more graphic and more violent than anything published in “Nights of Horror.”

And has society collapsed?

If anything, we’re healing. The violent crime rate is half of what it was in the ‘90s before the internet, and while the violent rape rate is about equal to that of the ‘90s on paper, this is largely due to the legal definition of rape being broadened in 2013 — the violent rape rate was declining until this change, suggesting that violent sexual assaults have become less common. Correlation isn’t causation, and I’m not saying that the widespread access of porn is responsible for these declines. But it definitely hasn’t led to the violent depravity feared in the 1950s.

Most people have sexual desires, whether they understand these desires or not, whether they want these desires or not. And many people have kinky sexual desires — about two-thirds of women and one in two men have rape fantasies, while over half of Generation Z’ers have BDSM fantasies. Even when raised in the heavily censored, white-picket-fence 1950s with as little access to pornographic material as humanly possible, a lot of people still have these thoughts. The question is: Are people shown how to engage in these fantasies in healthy, consensual ways, or are they given no indication that these thoughts are normal, no acknowledgment that there’s nothing wrong with them, and no clue how to engage with these attractions in a responsible way?

Scrubbing sexuality from our books has never worked, not in the 1950s, where “Nights of Horror” became famous due to its suppression, and not today, where the unbridled internet can provide us with anything our heart desires. People are sexual beings, and books can reflect this reality, giving us outlets for desires we can’t actualize, new ideas for things to try in the bedroom, and, most importantly, an acceptance that we and our desires — whether we’re gay or straight, kinky or vanilla, monogamous or poly — are normal and nothing to be ashamed of. Censorship can make people confused about their sexuality, but it can’t make their sexuality go away. If it could, we never would have gotten sexy Superman.