What has drawn poets to the sestina all these years?

Stephen Burt offers that “the sestina has served, historically, as a complaint” and, too, poses a question: “Does it still?” (219). Which, I suppose, is a question I must consider too when wondering why writers seem so infatuated with the form to this day. Are poets today turning to the sestina simply as a form to satirize or the bearer of “arbitrary procedural constraints,” so divorced from their own tradition, as Marjorie Perloff suggests (Burt, 222)? Or is there something else inherent in the form that contemporary poets are seeking out? Through three contemporary poems — “Sestina” by Elizabeth Bishop, “Sestina” by Ciara Shuttleworth, and “Sestina in Prose” by Katharine Coles — I hope to explore the function of the sestina itself and how it informs poetry even now, from traditional to truncated. I do not believe it to be “arbitrary.”

First, let us address tradition. Arnaut Daniel is credited with the founding of the form, first writing his sestinas in 12th century France. The movement of the form out of France was attributed to the monoliths of Italian poetic history, Dante and Petrarch, and Sir Philip Sidney found it pertinent to introduce it into English in the 15th century (Huyssteen), 300 years after its inception. Burt Steven mentions the 1930s revival of the form led by W. H. Auden in his article “Sestina! or, the Fate of the Idea of Form”; he also quotes many other writers on the sestina in the 1950s, such as American journalist and author Jimmy Breslin deriding the decade as “the age of the sestina” and anthropologist Edward Brunner, in his book “Cold War Poetry”, saying that poetry collections then “seemed incomplete without a sestina” (219).

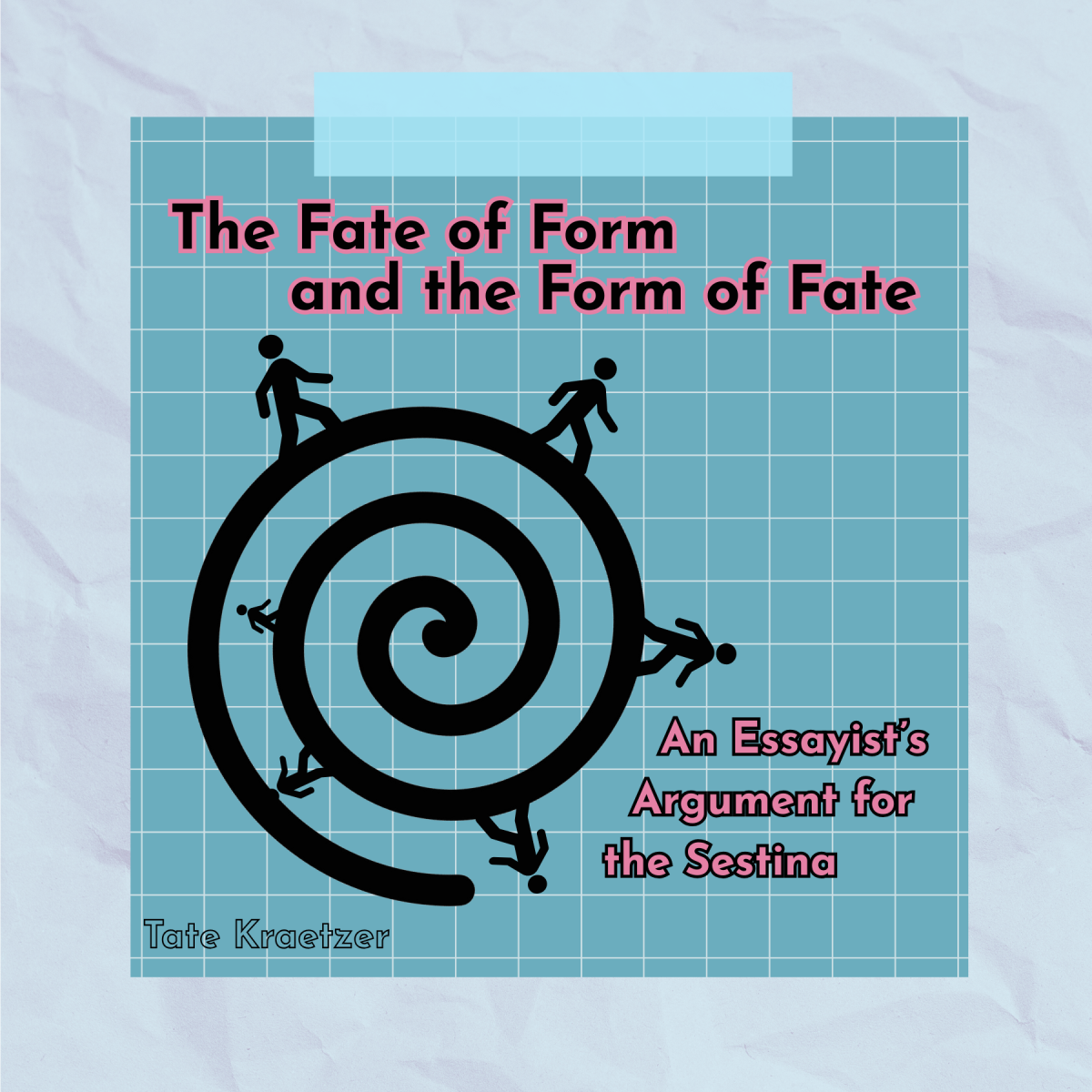

The sestina itself seems an innocuous form. Composed of six sestets and one tercet, it is 39 lines long, with a refrain in place of a rhyme scheme. Said refrain is heavily formulaic; in fact, numbering the consecutive end words of the first stanza 1-6, you observe a spiral pattern, helpfully illustrated here by Phil Wink:

The final three lines are not included in this visual, but are no less formulaic. Referred to as either the envoi or the tornada, the American Academy of Poets states that the end word pattern of this tercet is either “ECA or ACE” — or, in more uniform terms, 531 or 135 — with the other three end words BDF (or 246) appearing in the final three lines as well. The poets I’ve reviewed seem to respect this equation far less than that of the preceding sestets.

Elizabeth Bishop, born 1911 and died 1979, is remembered today as one of the most important poets of her time (“Elizabeth Bishop”). Her 1965 poem “Sestina” is beautiful in its tradition: 39 lush lines, classical end word order, with six sestets and one EDA (or 541) envoi. The poem broaches the topics of orphanhood, grief, and even poverty; the first word of the poem is “September” — a time of both death and new beginnings (1). The end words are illustrated in lines 1-6 below in bold, which I have added:

September rain falls on the house

In the failing light, the old grandmother

sits in the kitchen with the child

beside the Little Marvel Stove,

reading the jokes from the almanac,

laughing and talking to hide her tears.

The exclusive use of nouns at the ends of lines makes the house, the overarching location of the poem — both the first and the last end-word of the entire piece — feel empty, barren. Taking place in “the failing light” of the kitchen in the early autumn “rain,” there is already something despondent about the narrative before the grandmother is said to be “hid[ing] her tears” (2,1,6). Even though the grandmother in line 2 begins, on the page, above the child in line 3 — covering, protective, much like the house is a barrier for the rain — there is already distance between them: A grandmother is inherently defined by her relationships, that she has a kid or kids and that they have children of their own, but the child is untethered: There is a generation lost between the two, a connective force overcome. The sestina allows us to physically track this distance throughout the poem; as the end-word order changes, so too does the separation between these characters, expanding to as large as 4 lines (31 and 35). By the time the poem reaches its envoi, we encounter a literal becoming smaller, a folding in of the form from six lines to three — yes, there is a loss of fullness, but that is understood to have been a consequence of the grandmother’s “equinoctial tears” (7). Two times a year, she cries; two times a year, she must contend with an anniversary of grief; two times a year, she must remember the two she has lost. This family has shrunk, there is no denying that, but they cannot keep pretending at fullness, there must be a moment of reorganization, of re-understanding. The final tercet sees the grandmother above the child once again, more firmly planted within the nouns of the house, restructured into a new space, a new situation (38 and 39). “The child draws another inscrutable house” — something new, unknown, in need of cultivation; as the almanac says: It is “time to plant tears” (39, 37).

The sestina offers not only an exploration of distance, but of change. Each iteration of the end words places them in a new context, a new understanding — they fluctuate in relation to each other until balance is achieved. In this way, the sestina is well suited to discussions of grief. The narrative here is chronological, a simple scene in a curiously empty house shared by grandmother and child, but the reordering and repetition of the end words allows for a resistance to time. Unlike the longer refrains observed in pantoums or villanelles, the chaos does not come from being stuck in the same pattern of thinking, but from being forced to reorganize — being forced to change and become new. It’s uncomfortable to be pulled suddenly, back and forth, between the same images, to have no rhyme scheme but sounds you keep coming back to in dissonant order, just as it’s uncomfortable to settle into a new form.

Ciara Shuttleworth, born in San Francisco, is a modern poet still on the scene today. Her 2016 poem “Sestina” is an exercise in the form starved to its barest bones: 39 single word lines, composed of only six words used seven times in the traditional end word order, with six sestets and one BDF (or 246) envoi. The poem is, ostensibly, a break up poem — and in that way, as in that of Bishop, it is a poem about both love and grief. The end words are illustrated in lines 1-6 below in bold, which I have added:

You

used

to

love

me

well.

Strange, right? That’s a whole lot of bold. And, really, that is what this poem is: bold. A courageous taking on of form, of synthesizing the intent and effect of the sestina on a single sentence, a single event. The two most interesting words to me in this poem are “you” and “me” — both the audience and the speaker are firmly established in lines 1 and 5, and both function independently, but tellingly. “You” is capable of being both the subject and the object of a sentence, while “me” is capable simply of being the object of a preposition, something things are done to rather than by, something passive. So, it’s especially interesting to see how the speaker, and the poet, shift the language and punctuation around the word “me” to make it capable of being the subject as well, giving it agency as the speaker works through their breakup and, by nature of the fluctuating order, shifts their perspective on blame and distance. Like in Bishop, distance plays a large role in this sestina as the distance between the ex-lovers expands and contracts, again reaching as large as 4 lines (19 and 23). By the time the poem reaches its envoi, we are struck with a harsh difference between the two poems: Shuttleworth’s speaker gains fullness rather than losing it. The poem expands into three lines of two words, rather than six lines of one. In it, the “you” and the “me” are cemented as having one line of separation between them, but it feels less like distance here — they are united in the middle by the words “to love” (37-39). Due to the nature of trying to fit six single words into a form reliant on six lines per stanza, Shuttleworth is more beholden to end-stopped lines than Bishop in order to make the selected “end words” function together in every order. This intense use of end-stopped lines makes the reading experience uncomfortable and new, but also plays on the rhythm of stuttering to new conclusions through speech. As the speaker reconsiders the relationship in terms of action and intent, the poet allows the final sentiment to be that of love. Even though the verb “used” is in the past tense, the poet allows the “love” to be an active infinitive, something done to others, always in the present.

The sestina allows for one of the most powerful moments in the poem to come in line 34 and 35. Put simply, the speaker accuses their ex of using love, though they do say they used it well, and the speaker admits: “Me, / too.” It’s so simple, but so strong, and would likely be stripped of its power had it not come in a form in which the poet is constrained to using the same words ad nauseam. The poet finds a way to not only bear half the blame, but place the word “me” in the position of the subject, refusing the passivity the speaker was seeking for themselves at the beginning. This is a form of upheaval, of coming to a moment of growth, change, and, within that, grief. The speaker settles into their conclusion, and it is the same statement they gave in the first stanza but reworked, reconsidered, stabilized; the square-like tercet feels more secure than the wiry sestet — indeed: “You used / to love / me well” (37-39).

Katharine Coles, born in 1959, is a modern poet who served six years as the state of Utah’s Poet Laureate. Her 2019 poem “Sestina in Prose” is an example of what the Academy of American Poets refers to as a modern inclination towards the “contraction of the sestina form”: Composed of six long lines, with five repeating ‘end’-words, and the final (and shortest) line serving as the envoi. The poem is about struggle, strife, but also recovery and resetting. The “end” words are illustrated in line 1 below in bold (and underlined, more on that later), which I have added:

It was like climbing a mountain to those of us who’d climbed one. To the others,

it was like, I suppose, something else. In other words, we let everybody find

her own figure of speech.

Obviously, this sestina (though I’d argue it’s a “quintina” with five ‘body’ stanzas and one final envoi, consisting of five repeated words) is very different visually. Functionally, though, excepting the sestina’s love of sixes and replacing it with that of fives, the poem works the same. One notable difference is the way in which Coles approaches repetition. The invocation of the sestina form in the title involves the audience in building the form, encouraging them to seek the repetition inherent to the sestina form in a previously unknown way — Coles uses the freedom of prose to rely on association more so than refrain and, in doing so, brings the audience into the progression of the piece. The images are not only recontextualized, but changed, as they themselves fluctuate within the poem: “mountain” (1,2,3,4,5) turns to “crag” (6), “one” (1,2,3,4,5) turns to “two” (6), “else” (1,2,3,4,5) turns to “otherwise” (6), and “body” (1,2,3,4,5) turns to “burden” (6). But what of “speech” (1)? Here, we come back to the full underlined phrase “figure of speech” from line 1 — first, “speech” appears in the first two lines, as well as line 4, cementing it as an axiom of repetition, but it appears in line 3 as “metaphor, or even simile,” referencing the full phrase from line 1 and invoking two figures of speech. Again, in line 5, the full phrase is called upon when “speech” appears as “figure.” Perhaps my favorite iteration, though, is that of line 6: Twice, the line brings up speaking as a verb, in fact as an order — “say” and “talk” — both of which function as agents of repetition, but I would argue not as the true final form.

The speaker’s journey through the poem is learning that hiding behind figures of speech is limiting, inhibiting, that “the like-it-or-not-ness of the mountain pretty much [gets] between a body and her musing,” that “this struggle” is “no simple figure” (3,6,5). The circularity of the sestina form serves this poem well, allowing images to cycle, traumas to be refaced, in new contexts and ways, professing a growth in process and motivation. The alterations to the repetition allow for the poem to be a conversation, much like a support group circle, sharing struggles and working from the most base, beautified prose to the truth. So, I would argue, after grounding the poem to “your own two feet,” to a forced anti-loneliness and utter honesty, the final iteration of “speech” is “talk through your hat” — a figure of speech meaning to talk nonsense, especially about something one knows nothing about but claims to be knowledgeable of (6). Something the speaker and “I don’t care for” (6).

In my opinion, the main import of a sestina is circular images, but not circular thinking — the images, and presumably the speaker, grow and evolve with each iteration; it seems to be an exercise in reflection, analysis, and coming to an understanding — often, and most powerfully, with yourself. The throughline of these sestinas has been struggle and grief, and the form lends itself impeccably to those topics, but the main point of analyzing subjects like these in this form is growth. The same images, often the same idea, is reiterated in the final tercet, the envoi, but the tone is different — it is resolute. So, what has drawn poets to the sestina all these years? This exact moment of great understanding: Things are hard, they may even get harder, but goddamnit I will survive.

Works Cited:

Burt, Stephen. “Sestina! Or, The Fate of the Idea of Form.” Modern Philology, vol. 105, no. 1, 2007, pp. 218–41. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/587209. Accessed 19 Nov. 2024.

“Elizabeth Bishop.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/elizabeth-bishop. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

Huyssteen, Justin Van. “Sestina – Discover One of the Most Complex Poetic Forms.” Art in Context, 3 Nov. 2023, artincontext.org/sestina/. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

Kelly, Joseph. “Sestina, Elizabeth Bishop.” The Seagull Book of Literature, 5th ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2023, pp. 31-32.

Wink, Phil. Graphical representation of algorithm for ordering repeated words in a sestina. 14 May 2012.