“I tell you, monsieur, the world’s at an end. Never were there seen such breakings-up of the scholars! It’s the accursed inventions of the age that are ruining everything – the artillery, the serpentines, the bombards, and, above all, the printing-press, that German pest! No more manuscripts; no more books! Printing puts an end to bookselling: the end of the world is coming!”

“I believe you. See how velvet’s coming into fashion,” sighed the furrier.

— “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” 1831

It was early on a chilly autumn morning when The Atlantic article was suggested in my feed: “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” by Rose Horowitch. What was this? A lowly public school student like me was superior to the upper echelon of university pupils? Good golly, I had to read this! It was locked behind a paywall, but some kind stranger had posted a gift link online, allowing the article to break away from its (intended?) audience and into the lap of someone never expected to read it: an actual college student.

The article made many points I hadn’t considered before, such as how standardized testing has caused a push towards reading excerpts instead of full books in school, and how shortened attention spans caused by social media are making it more difficult for students to track necessary information in books. And I couldn’t ignore the stats the article published that suggested people — young and old — are reading less than they used to, inside and outside school (more on that in a moment).

But the article centered around a hypocrisy. Throughout most of the text, the abandonment of reading for fun by young people was used to “prove” that we’re in the midst of a reading crisis; it needs to be fixed, and fast, to give young people the ability to “stimulate … valuable thinking habits” and “cultivate a sophisticated form of empathy.” I don’t want to lose that! And yet, in the last few paragraphs, Horowitch pivoted suddenly to complaining about what our self-reported favorite books are: “Percy Jackson” instead of “The Iliad,” contemporary stories instead of the classics. In a baffling display of black-and-white thinking, she concluded with, “To understand the human condition, and to appreciate humankind’s greatest achievements, you still need to read “The Iliad” (instead of “Percy Jackson”) — all of it.”

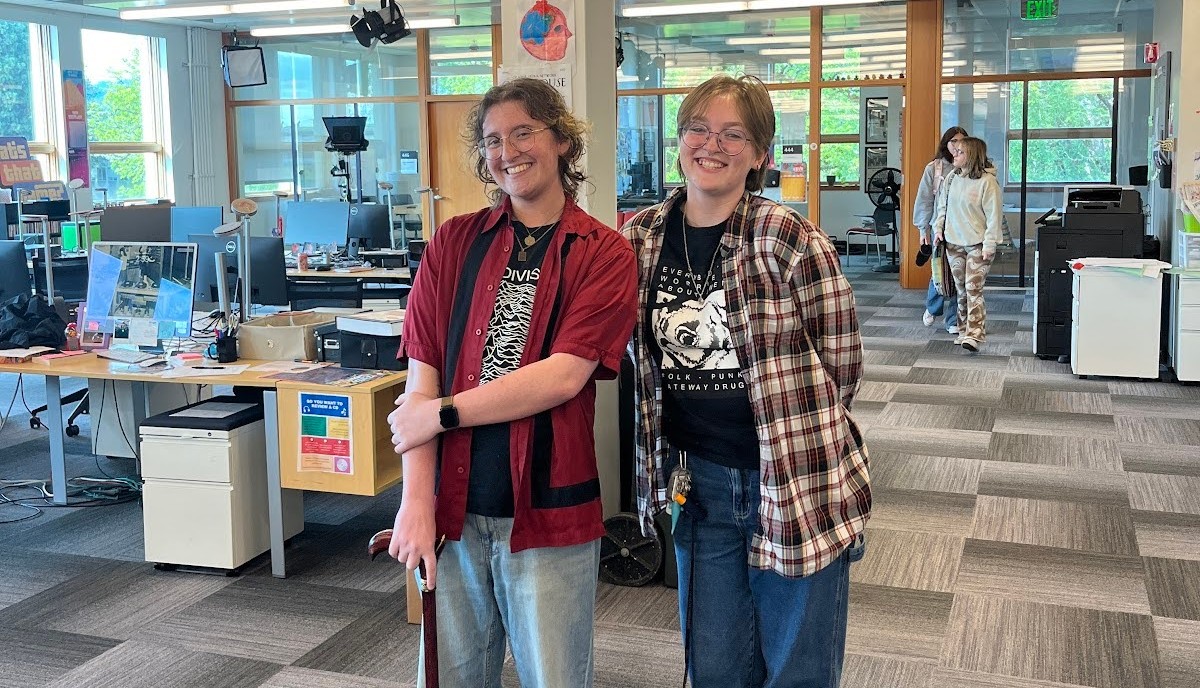

I’m going to take a moment to toot my own horn. If you’re worried about youth abandoning the art of reading (which, my default sarcasm aside, would genuinely be a problem), I’m your gal. I’m the Assistant Editor for my uni’s literary and art journal. I’m the Events Coordinator for Oregon State University’s Creative Writing Club. In my free time, I volunteer for a Hugo-winning literary journal, reading hundreds of short stories to review. I live, breath and sleep literature. And the most influential piece of media I’ve ever consumed? A NBC sitcom starring the voice actress of Anna from Frozen. It’s not that I haven’t read “The Iliad,” “Frankenstein,” “The Pentamerone,” “How to Kill a Mockingbird,” or any number of classics. It’s just that, while classics may have valuable messages to impart, books’ abilities to expand your mind and your heart are just as alive and well now as they were 200 years ago. And thank goodness they are!

If you’re a teacher or parent worried about the youths’ lack of interest in reading the classics for fun, relax. Take a deep breath. Here are some reasons, stemming from neither “atrophy or apathy,” that young people may prefer to read contemporary literature:

— The language: Writing styles and norms change over time. It’s not that young people can’t read classics, but most contemporary readers will find contemporary books easier to get lost in, and therefore more enjoyable to read.

— Changing social norms: “The Iliad” makes an interesting prerequisite for understanding the “human condition,” because my memory of reading it is dominated by the dread of seeing myself as a blank object through the story’s treatment of what few human women there were. It’s not that war and men’s intrafighting doesn’t represent a part of the human condition, but can you really blame women, people of color, queer people or any other person for wanting a “human condition” where they occasionally get to have fun?

— The background knowledge: Meaning doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and stories are written for the era in which they were created, with its specific collective consciousness. While anyone can read “Moby Dick,” a 21st century atheist with little knowledge of the Bible will likely miss references and messages that any reader in 19th century America would have picked up on, a problem they’re unlikely to encounter in contemporary literature.

— The relevance: I’m the last person to claim modern folks can’t learn valuable lessons from the classics, but there are some things classics can’t do. The most impactful non-fiction book I’ve ever read, “Being Mortal” by Atul Gawande, addressed the uniquely modern state of Western geriatric care and medicine head-on, speaking directly to my experience as a caregiver; a story written 40 years ago couldn’t do that. The most impactful fiction book I’ve ever read, “Kindred” by Octavia Butler, is a brutally honest confrontation with the centuries-long legacy of chattel slavery; while an author from the 19th century could write a book like that, it’s hard to imagine they’d get it published and cemented on library shelves. We exist in our era. There’s a benefit to reading books written for us.

This may seem like common sense, but the oblivion of Horowitch to the reasons young people may not be reading classics for funsies is concerning to me. Isn’t The Atlantic supposed to be one of the pinnacles of modern journalism? I’m a little worried that the biases of Horowitch’s interviewees, whose anecdotes and armchair observations made the bulk of the article’s “evidence,” was never addressed — of course, professors of classical literature like Nicholas Dames, Jack Chen and Daniel Shore have a vested interest in making fine literature seem like an endangered species that needs additional investment! Like the furrier of Hugo’s work, their income, job security and status depends on how much reverence we give the classics. This doesn’t mean there isn’t value in interviewing them, but did Horowitch, who interviewed 33 professors, really not have time to interview a single professor of contemporary literature or — groundbreaking, I know — an actual college student?

And this leads to my second concern. As Horowitch herself admits, there’s a long-standing tradition of fearmongering about young people’s reading habits. But I didn’t find any evidence in Horowitch’s article that young people’s reading habits specifically are worrisome. In paragraph 18, she mentioned that the number of people reading for pleasure overall has shrunken, which makes sense. People spend hours a day (on average) on social media, time we had to take from somewhere — and while young people may spend more time on social media than our parents and grandparents, we’re certainly not alone in sacrificing our time on the altar of Youtube. Why frame the entire article as “The youth! Oh no, we must save the foolish youth!” if we’re all in this mess together? Most importantly, for all the evidence Horowitch found to suggest that high school and college classes are not assigning as many full books to read as they once did, she never provided any concrete support for her claim that young people’s critical thinking skills are declining — a blinding omission in an article whose entire point is that young people “don’t know how to read.”

The purpose of this response is not to trash the classics or people who like them. I’ve learned a lot from the classics I’ve read, and I plan to read more. But it rubs me the wrong way to see a bunch of middle-aged writers and professors fearmongering about my generation’s lack of reading while also dissing the books we do read. Some of us like reading “The Pentamerone” in our free time; others prefer “Arcane” fanfics. And that’s okay! If you want us to read more, talk to us. Work with us and the books we’re finding valuable. And instead of running away with your fears, ground yourself in the facts and our lived experiences as much as yours. We can be worth listening to. I promise.